Mozambique / República de Moçambique – Let’s explore here

What’s it like in Mozambique?

Mozambique is a country in south eastern Africa on the Indian Ocean, very slightly larger than Turkey. It mostly consists of hills and highlands to the north, with some mountains to the south of the country. The highest point is Monte Binga, in the west of the country, on the border with Zimbabwe, at 8,004 ft (2,440 m) above sea level.

The country has a long and troubled history, being one of the least developed and poorest countries on the planet. It shares land borders with Eswatini, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

The population of Mozambique is around 35 million people (2024), over one million of whom live in the capital, Maputo.

A bit about the history of Mozambique

Early History and Indigenous Societies

Mozambique has a long history of diverse indigenous cultures. The area has been inhabited for thousands of years by various ethnic groups, including the Bantu-speaking peoples, who developed complex societies with rich agricultural practices, trade networks and kingdoms. The region was also influenced by various outside cultures due to its coastal position along the Indian Ocean, including contact with Arab traders, Swahili city-states, and later the Portuguese.

Portuguese Colonisation

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to establish a permanent presence in Mozambique. In 1498, Vasco da Gama’s voyage to the Indian Ocean marked the beginning of Portuguese influence in the region. By the late 16th century, Portugal began to establish trading posts and forts along the coastline, focusing on trade in gold, ivory and slaves. Mozambique became an important part of Portugal’s empire, but it was not as economically developed as other Portuguese colonies like Brazil.

In the late 19th century, Portugal formally annexed the region, creating the colony of Mozambique. The colonial administration was characterised by a system of economic exploitation, primarily focused on cash crops like cotton and sugar, and the forced labour of the indigenous population. The Portuguese maintained control over the colony through military force, and there was little significant investment in infrastructure or development in the interior of the country.

Nationalist Movements and the Struggle for Independence

During the mid 20th century, as African nations began to push for independence, Mozambique saw the rise of nationalist movements. The two main groups fighting for independence were the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO), founded in 1962, and the Mozambique National Resistance (RENAMO), which would later emerge as a key player in the country’s post independence conflict.

FRELIMO, led by Eduardo Mondlane and later Samora Machel, waged a guerrilla war against Portuguese colonial forces, primarily operating from neighbouring countries like Tanzania and Zambia. By the early 1970s, Portuguese colonial rule was in decline due to political and economic crises in Europe, including the Carnation Revolution in Portugal in 1974, which led to the end of Portugal’s colonial empire. Mozambique gained its independence from Portugal on 25 June 1975, with FRELIMO in power. Samora Machel became the first president of the newly independent nation. The country was initially hopeful, with Machel’s government seeking to create a socialist state, focusing on land reform and education.

Post-Independence Challenges and Civil War (1975–1992)

Following independence, Mozambique faced significant challenges. FRELIMO’s policies, including the nationalisation of land and industry, were met with resistance, particularly from rural populations and the private sector. RENAMO, a group initially backed by the Rhodesian (later Zimbabwean) and South African governments, launched an insurgency in the late 1970s, leading to a brutal civil war. RENAMO received support from white-minority regimes in southern Africa, while FRELIMO was backed by the Soviet Union and other socialist states. The civil war devastated the country, resulting in the deaths of an estimated one million people and displacing millions more. The conflict lasted for nearly 17 years and had a profound impact on Mozambique’s economy and infrastructure.

Peace Agreement and the Transition to Multi-Party Politics (1992–2000s)

In 1992, after years of negotiations, the Rome General Peace Accords were signed between FRELIMO and RENAMO, officially ending the civil war. The peace agreement included provisions for demobilisation, political reforms and the establishment of multi party elections. The first multi party elections were held in 1994, and FRELIMO, under the leadership of Joaquim Chissano (who succeeded Samora Machel after his death in a plane crash in 1986), won a plurality of votes, with Chissano becoming the country’s second president.

The end of the civil war marked the beginning of Mozambique’s transition from a one party socialist state to a more democratic, market oriented society. Economic reforms were implemented, and Mozambique experienced significant growth during the late 1990s and early 2000s, particularly in sectors such as mining, agriculture and tourism. However, the country remained deeply affected by the legacy of the civil war, with poverty, weak institutions and inequality continuing to pose challenges.

Economic Growth and Political Stability (2000s–2010s)

The 2000s saw Mozambique experience a period of rapid economic growth, driven by foreign investment, particularly in natural resources such as coal, natural gas and titanium. The discovery of large natural gas reserves in the north of the country, particularly in the Rovuma Basin, brought international attention and promises of significant economic development.

In the political sphere, FRELIMO continued to dominate, but RENAMO remained a significant opposition force, although its influence declined after the peace agreement. However, tensions between FRELIMO and RENAMO flared up again in the early 2010s, with sporadic violence and clashes between the two groups. In 2014, after years of negotiations, a new peace agreement was reached, which led to the disarmament of RENAMO forces and the integration of its fighters into the national army.

In 2015, Filipe Nyusi, a member of FRELIMO, became president. During his presidency, Nyusi focused on continuing economic reforms, improving infrastructure and addressing corruption, although challenges related to poverty, corruption and inequality persisted. Mozambique’s growing debt crisis in the mid 2010s, due to hidden loans taken out by state-owned companies, led to significant economic and political turmoil.

The Hidden Debt Crisis and Recovery (2016–2020)

In 2016, it was revealed that Mozambique had secretly borrowed $2 billion through loans arranged by state-owned companies. The scandal, known as the ‘hidden debt crisis’, led to a suspension of international aid and a sharp decline in investor confidence. The government was accused of corruption and mismanagement, and several senior officials were arrested in connection with the scandal.

Despite the financial crisis, Mozambique continued its efforts to attract foreign investment, particularly in the natural gas sector. The government worked to restructure its debt and regain the trust of international donors and investors. By the late 2010s, the economy showed signs of recovery, with growth rebounding in sectors like mining and energy, although challenges remained in addressing inequality and corruption.

Ongoing Conflict and the Rise of Islamist Militancy

In recent years, Mozambique has faced increasing challenges from Islamist militants in the northern province of Cabo Delgado. Since 2017, a group known as Al-Shabaab (unrelated to the Somali group of the same name) has been responsible for a growing insurgency, targeting villages, government forces and foreign companies involved in gas projects. The insurgency has displaced hundreds of thousands of people and disrupted economic activities in the region. The government has struggled to contain the insurgency, and Mozambique has sought assistance from regional and international partners, including Rwanda and the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

Mozambique road trip

Our Mozambican road trip is part of a much larger African road trip.

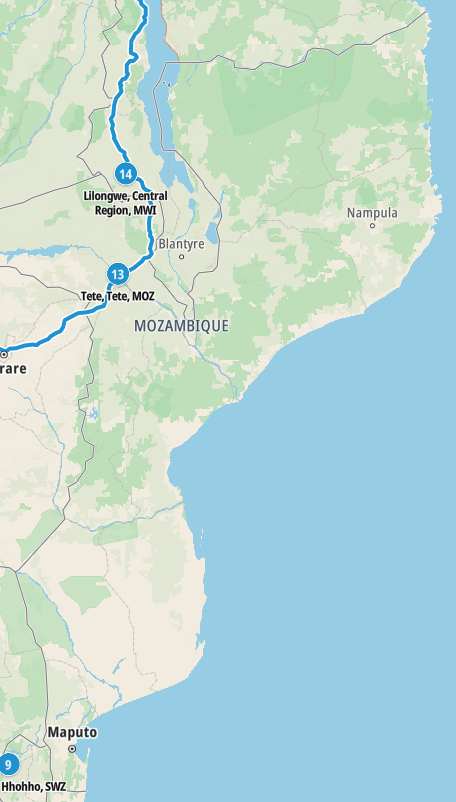

Map of our road trip through Mozambique

Our current planned road trip through Mozambique takes us from Zimbabwe, across the north of the country, before heading in to Malawi. No doubt we’ll explore the country much more than this continent-spanning short route shows, in particular checking out the capital, the coast and inland.

Hopefully our journey will improve our knowledge of this intriguing and beautiful country, and enable us to meet some interesting people. We’ll be updating this page at that time – don’t forget to check back 🙂

What’s it like to drive in Mozambique?

They drive on the left hand side of the road in Mozambique. In the main, roads are very poor, with many being unsurfaced dirt tracks. Driving standards are also poor.

Do you require an international driving permit in Mozambique?

We’ve created a dedicated page to driving abroad, which answers this question, and more, which you might find helpful.

Can you use your UK driving license when driving through Mozambique?

We’ve created a dedicated page to driving abroad, which answers this question, and more, which you might find helpful.

Do I need a carnet de passages to drive in Mozambique?

We’ve created a dedicated page to driving abroad, which answers this question, and more, which you might find helpful.

What currency do they use in Mozambique?

In Mozambique they use the Mozambican Metical. Cash is widely used. The US dollar, South African rand, and the euro are widely accepted. The use of credit / debit cards becoming more widely accepted outside of the capital, Maputo. Travellers cheques are not readily accepted. There are some ATMs throughout the country.

You should make yourself aware of the amount that your bank charges you for using credit and debit cards abroad. Often credit cards are cheaper for purchasing items directly, and for withdrawing cash from ATMs.

What language do they speak in Mozambique?

They mainly speak Portuguese in Mozambique. They also speak many Bantu languages. English is not widely spoken.

What time zone is Mozambique in?

Remember, when you’re planning your next trip to take a look at what time zone it’s in.

Do I need a visa to visit Mozambique?

We’ve created a dedicated, more comprehensive page on visas, which you should find helpful. Check it out!

Is wild camping legal in Mozambique?

Yes, wild camping is fine in Mozambique.

What plug / socket type do they use in Mozambique?

In Mozambique they use plug / socket types C, F and M.

Health issues in Mozambique

Is it safe to drink water in Mozambique?

No, it is not safe to drink tap water in Chad. Bottled water is readily available throughout the country.

What vaccinations are required for Mozambique?

This NHS website is kept up to date with all relevant information on vaccinations in Mozambique.

Phones in Mozambique

What is the country calling code for Mozambique?

The country calling code for Mozambique is +258

What are the emergency phone numbers in Mozambique?

- The emergency number for police in Mozambique is: 119

- In Mozambique, the emergency number for ambulance is: 117

- The emergency number for fire in Mozambique is: 198

If you’ve got some useful info that you’d like to share, let us know!

And don’t forget to check out all the other pictures!